Welcome to Ph.D. Voices, a monthly series in which Ph.D. candidates share their research with the antitrust world. This month’s voice is Alba Ribera Martínez, Ph.D. candidate at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

****

International Cooperation at Crossroads with Comity

Enforcement is key to understanding an effective application of competition law. In digital markets, as much as in any other sector, competition authorities must deal with the extraterritoriality of business conducts and mergers to enforce their decisions effectively. Public international law provides the principle of territoriality to establish a sovereign State’s exclusive jurisdiction over an individual or a particular case. Unfortunately, this principle is inadequate to capture the scope of economic conduct because anti-competitive effects usually radiate into different jurisdictions with different legal standards and enforcement priorities.

From the perspective of domestic law, the principle of international comity was first proposed in the US doctrine as a solution for jurisdictions to maximise their joint interests by dissipating existing law conflicts. Through comity, a State defers before another State’s decisions. In other words, comity is an informal channel to maintain amicable working relations with other States, which can play out as a principle of recognition or as a principle of restraint.1Eleanor M. Fox, ‘Antitrust Without Borders: From Roots to Codes to Networks’ in Andrew T. Guzman (ed.), Cooperation, Comity, And Competition Policy (Oxford University Press, 2011).

In terms of competition law, this would mean that a competition authority can: i) assert its jurisdiction over another country to remedy anti-competitive conduct committed in another territory; or ii) abstain from intervening in a given case to avoid interfering in the interests of foreign jurisdictions.

On paper, comity seems quite straightforward to apply to competition law. However, following the OECD’s findings in 2022, competition authorities generally refuse to use the instrument at the international level due to a lack of experience with it.

Domestic Law Transposed into an OECD Recommendation

The principle of international comity is quite difficult to conceptualise, as it has many different manifestations across jurisdictions. Although comity can overlap with rules of international law, it derives from domestic law. Its provisions derive from each State’s discretion to cooperate through a principle of recognition/restraint before foreign States’ legal standards and jurisdictions. In this sense, comity does not impose a sense of legal obligation upon States. Instead, it presents the option for States to exercise deference, when needed, to avoid substantial contradictions in enforcement.

In the US, comity was first used as an instrument to recognise jurisdiction in favour of US courts regarding anti-competitive behaviour that took place abroad (principle of recognition).2 First established in United States v. Aluminium Co of America (Alcoa), 148 F. Supp. 2d 416 (2nd Cir 1945) and then passed into law through the Foreign Trade Antitrust Improvements Act. 15 USC §6a … Continue reading However, several rulings of the Supreme Court instrumentalised comity as a limitation to the extraterritorial reach of American antitrust law (principle of restraint).3Following findings from William S. Dodge, ‘International Comity in American Law’ In the broadest terms, all these rulings agree that a conflict of laws should exist between two different competition law regimes to deem comity applicable.

In the EU, the Court of Justice held that the principle of restraint deriving from comity could not apply to the relations between the Member States.4Case C-185/07, Allianz SpA v. West Tankers Inc., 3 W.L.R. 696 (2009); Case C159/02, Turner v. Grovit, 2004 E.C.R. 1-3565; Case C-116/02, Erich Gasser GmbH v. MISAT Srl, 2003 E.C.R. 1-14693. Instead, the compulsory principle of mutual trust applies at the EU level and should be followed according to the provisions of the Brussels Convention.5Following findings from Christopher R. Drahozal, ‘Some Observations on the Economics of Comity’.

The Court demonstrated the closest approximation to comity in EU competition law in the Gencor ruling. In the judgement, the Court examined whether the principle of non-interference was breached due to the competition authority’s decision to prohibit the merger of two South African undertakings. The Court backed the EC’s decision based on the sovereign State’s passivity before the EC’s scrutiny over the merger during the administrative and judicial proceedings.

Against this background, in 2014, the OECD issued a Recommendation to enhance international cooperation and ensure consistency between the enforcement responses of competition authorities against potentially conflicting cases and scenarios. However, the OECD introduced particularly bland and insubstantial provisions for the competition authorities to apply under the principle of traditional comity. They come quite far from the existing precedent in both the US and the EU. The recommendations include suggestions and notifications between the interested competition authorities without considering substantive rules regarding relevant elements to apply the principles of recognition or restraint.

The following table compares the existing rules and the interpretation of case law surrounding comity in antitrust:

| United States | European Union | OECD | |

| Content of comity | Extraterritoriality of antitrust rules (conducts and merger) | Jurisdiction over extraterritorial conducts | Relations between NCA’s |

| Instrument | Conflict of laws | Principle of non-interference | Full and sympathetic consideration + timely notice of significant developments |

| Legal analysis | Irreconcilable and blatant effects of conduct in US jurisdiction | Sovereign State’s intervention in the merger + proceedings | N/A |

| Legal consequence | Grounds to dismiss | Ground of appeal (lack of jurisdiction) | N/A |

The OECD reported back in its 2022 Report to the Council on the Recommendation’s implementation, and the results were discouraging. Up to 60 per cent of the OECD’s adherents declared they did not use the Recommendation’s comity provisions. Experience with comity outside of already existing regional networks was scarce and uneven. Along the same line, adherents to the OECD expressed that international enforcement cooperation is not possible due to legal limitations and differences in legal standards across jurisdictions. Thus, comity is not a solution to enhance international cooperation concerning cross-border anti-competitive behaviour and mergers. Only a few cases at the Global scale have applied comity under the provisions of bilateral agreements, especially in the form of comity as a principle of restraint. The same could apply to enforcement in digital markets, namely in mergers, where competition authorities have construed piled-on remedies through their intervention within the same case.

A Race-to-the-top towards a Stringent Enforcement Policy

The Facebook/Giphy merger is a great example of the consequences of conflicting and successive interventions by different competition authorities in the same case.

On 15 May 2020, Facebook completed the $400 million acquisition of Giphy. The merger went under the radar of the Federal Trade Commission and was not subject to US scrutiny. However, the merger was subject to review in three different proceedings under different legal standards: before the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (since 8 June 2020), the Austrian Federal Competition Authority (since 20 July 2021), and the UK’s Competition & Markets Authority (since 9 June 2020). The ACCC’s proceedings are still pending, whereas the Austrian Federal Competition Authority cleared the merger with conditions imposed,6The Supreme Court confirmed on 24 June 2022 the competition authority’s conditional clearance of the merger. and the CMA blocked the acquisition altogether.

Not one of the national competition authorities considered applying the principle of international comity. In their rulings, the Courts did not review whether these competition authorities should have applied comity, either.

The ACCC and the CMA started their proceedings a day apart and applied their supply test thresholds as the triggering event toward the constitution of the extraterritorial reach of their antitrust provisions. Following the OECD’s Recommendation, the CMA and ACCC should have notified each other of the initiation of merger proceedings concerning the same case, given that both jurisdictions adhered to the OECD’s Recommendation.

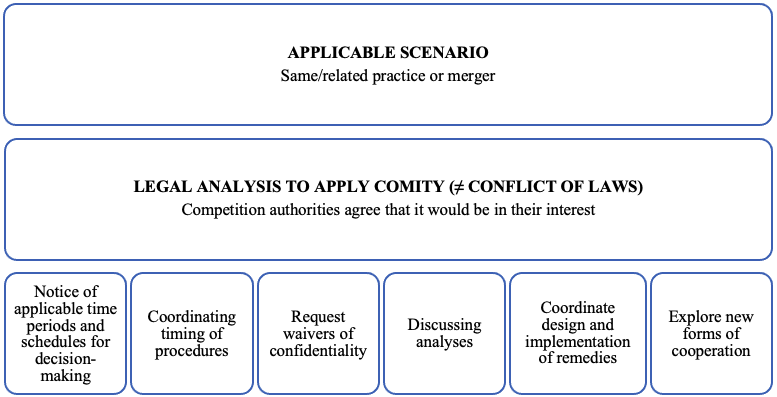

According to the OECD’s Recommendation, competition authorities should have applied the following analysis:

Although the reviews concerned the same merger, the applicable legal analysis hindered the effective extraterritorial application of antitrust rules, impacting both jurisdictions and worldwide consequences. The ACCC and CMA decided that it was not in their interest to coordinate efforts to reach an agreement on the outcome of the merger. The duplication of enforcement and the possibility of applying conflicting approaches and outcomes to the same merger did not outweigh their decision.

Given that competition authorities do not apply comity and do not coordinate their efforts in enforcement, cases are resolved in parallel by different competition authorities. The result is that the competition authority that imposes the most stringent remedy to the case absorbs the rest of the authority’s efforts. As for Facebook/Giphy, the CMA’s decision to block the merger seized the Austrian authority’s enforcement to clear the merger with conditions. The resources allocated at the Austrian level to the merger could have been used in other cases. To avoid further duplication of enforcement, an adequate blueprint should be drawn up to ensure that comity can be effectively applied

Proposal for the Expansion of the Recommendation

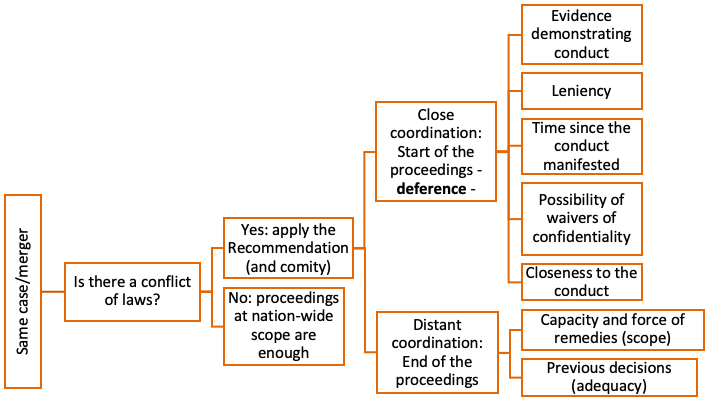

A clear framework should be defined at the OECD level, expanding on the current Recommendation’s content. The international organisation may adopt some of the few takeaways that both the US and EU have established in their respective jurisdictions to deem comity applicable. The proposed framework would apply as follows:

First of all, the Recommendation should define the concept of conflict of laws in terms of antitrust. Not all divergence in enforcement should fall within the scope of comity, and it should not be left to the competition authorities’ discretion, either. For instance, if the same case is analysed in different jurisdictions considering only nationwide conduct, all of them should, in principle, be capable of applying their legal standards to the case in their respective jurisdictions. As long as digital markets are concerned, this situation will seldom apply, so coordination between competition authorities will be as useful as ever.

Once a potentially conflicting situation is detected, the Recommendation should establish two different paths open to competition authorities, so that they can decide on the intensity of coordination between them. The Recommendation must acknowledge the possibility that both close and distant coordination between authorities is feasible through comity.

In the first case, close coordination between NCAs may take the form of outright deference to avoid conflicting and pile-on remedies in the same case. To this end, the Recommendation should list a range of different factors, so that competition authorities have their way paved to start informal contact among them to defer in favour of one or another in the initial stage of the proceedings (for instance, progress within the same proceeding, waivers of confidentiality, time since the conduct has manifested within the market). Regarding the Facebook/Giphy example, this could have meant that the authorities analysing the merger should have determined at the outset the best-positioned authority to analyse the merger, to avoid subsequent antitrust scrutiny from three different authorities.

In the second case, comity can be considered at the latest stage of their respective sanctioning proceedings, i.e., the imposition of fines/remedies, so that they, at least, are coherent with one another and can contribute to recovering the normal functioning of the market. Following the Facebook/Giphy merger, the CMA could have entered into dialogue with the Austrian authorities to factor into the analysis the conditions they imposed on the merger when deciding to block it. Perhaps the merger prohibition could have been curtailed by expanding on the conditions imposed by the Austrian authorities without the need to contradict the decision to clear the merger.

With this framework in mind, comity can be rescued from oblivion into the international landscape to enhance enforcement and competition policy, especially for those cases in digital markets where competition authorities assert their jurisdiction over cases with major repercussions.

***

Citation: Alba Ribera Martínez, Too Much, Too Many: The Principle of International Comity in Digital Markets, Network Law Rev. (October 21, 2022)