Dear readers, the Network Law Review is delighted to present you with this month’s guest article by Axel Gautier, Professor at the Department of Economics of HEC Liege, University of Liège.

***

Over the last two decades, the largest digital platforms have experienced incredible growth, reaching millions of users, developing many new products and technologies, and collecting enormous profits. This process builds upon both internal and external growth. Indeed, to develop their digital ecosystem, the main platforms have massively acquired other companies, mainly young startups. For startups, the prospect of being acquired by a larger platform became an interesting alternative to IPO. In recent years, it has been documented that acquisition has become the main exit route for startups (Ederer and Pellegrino, 2023).

To give a more precise idea, we identified 329 acquisitions by the five largest US digital firms (Amazon, Alphabet, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft, called hereafter the GAFAM) for the period 2015-2021. To be more concrete, during this period, Microsoft and Google made more than one acquisition per month. If some of those acquisitions received a lot of public exposure and were scrutinized and cleared by competition authorities in nearly all cases, most of the acquired companies were young tech startups; in our sample, the median age is less than five years. Little is known about the development of these startups, their products, their technologies, and their employees after their acquisition. Our research intends to fill this gap.

The question is of prime importance as there are many discussions and debates about killer acquisitions in the digital economy. A killer acquisition (Cunningham et al., 2021) refers to the acquisition of a competitor by a large firm that, later, eliminates the competitive threat by terminating, or said differently, killing the acquired product. When the purpose of an acquisition is to eliminate a potential competitive threat by killing the product that the startup develops, the acquisition is obviously detrimental to consumers, competition, and welfare, and it should be prohibited.

But firms may have other reasons for acquiring a startup: to integrate its product into their ecosystem, its network of users, its technology, its staff, etc. Screening between different acquisition motives is complicated, especially at the early stages of the startup’s life when the products and the business models are still under development. Therefore, evaluating correctly the threat to competition is far from being obvious.

In a recent paper, co-authored with R. Maitry, ‘’Big tech acquisitions and product discontinuation’’, published in the Journal of Competition Law and Economics (JCLE), we look at the evolution of the acquired companies after they have been taken over by one of the five above mentioned big tech (or GAFAM). The idea is to look at the evolution of the main product of the acquired company post-acquisition.

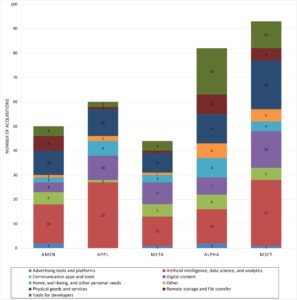

In our paper, we systematically review the acquisitions by the GAFAM for a period of 7 years, spanning from 2015 to 2021. For each company, the products and services are classified according to their purpose, using the classification developed by Argentesi et al. (2021). The classification in nine different clusters is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Acquisitions by the GAFAM (2015-2021), classified by cluster

What is immediate from the figure is that the acquisition of AI-related companies is massive and represents almost 30% of the total, with all firms equally active. We can also observe that despite being active in different fields, the acquisition strategies of the five firms are relatively similar. We observe that firms do not acquire massively in the product clusters in which they hold a strong market position. Alphabet and Meta, for instance, acquired a few companies in the advertising segment, where they are collecting the largest part of their revenue. They also acquire a lot in the business lines they try to extend to and where they compete fiercely, like digital content or cloud services. For those interested, we provide further analysis and additional data in the JCLE paper.

In the literature, many papers have shown that the majority of the acquired products have been discontinued post-acquisition. Gautier and Lamesch (2021) show that most of the acquired products were no longer available under their initial brand name after an acquisition by a big tech. Affeldt and Kesler (2021) show that half of the apps available on the Google Play Store and acquired by one of the GAFAM are discontinued post-acquisitions and that the remaining apps collect more user data. Eisfeld (2023) studies startup acquisition in the software industry. She shows that 57% of the acquired products have been discontinued under their original brand name after the acquisition. This percentage increases further when the acquirer is another software company and reaches 80% when a GAFAM acquires the product. So, there is a lot of evidence that acquired products are discontinued. Discontinuation as a stand-alone product is not necessarily detrimental as the product could be integrated into the acquirer’s ecosystem under a different name or format. We contribute to this literature by looking in more detail at the evolution of the products, and we introduce a new classification that goes beyond the dichotomy of continued/discontinued.

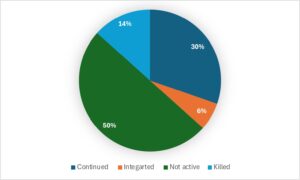

Next, we make a second classification of four different categories, depending on the evolution of the product after the acquisition, and we develop a rigorous procedure for doing the analysis. First, a company is said to be continued if it is still active, offers products under its initial brand name, and maintains an independent website. Many of the game studios acquired by Microsoft are, for instance, classified under this category. Second, a company is said to be integrated if its products are still offered, eventually under a different name, but its website is now part of the acquirer. Amazon, for instance, has integrated many acquired companies into its cloud business. Third, a company is said to be killed if the acquirer or the acquired company announced that the product will no longer be supplied or maintained. For instance, in 2022, Apple announced that the services provided by Fleetsmith will no longer be available to users. Fleetsmith was a startup that helped IT manage Apple devices remotely, which Apple acquired in 2020. Finally, the company is classified as inactive if its products are no longer offered and its website is deactivated, but there is no explicit announcement that the company or its product has been discontinued. The following figure shows the number of companies in each category, out of 300 for which we managed to recover the information.

Figure 2: classification of acquired companies post-acquisition in four categories based on 300 observations

What is immediate from the figure is that the majority of the products have disappeared, with only 30% that continued to be commercialized under their initial name and 6% that are explicitly integrated into the acquirer’s ecosystem. Most products are classified as inactive, as it is impossible to recover any information about their recent development. And 14% of the products have been explicitly discontinued by the acquirer. This evidence suggests that product acquisition is not the main purpose of the acquisition. The acquirer might be more interested in the users, the staff, or the technologies developed by the startup, and competition authorities should take that into consideration in their merger review.

When the acquirer terminates or discontinues a product, it is not necessarily to eliminate an anti-competitive threat. The product might also be a commercial or a technical failure, or it could become obsolete. In our data, it is impossible to screen between the different explanations. There is a large number of products that are becoming ghosts after they enter the big tech ecosystem.

To go further, in a companion paper, we look at the evolution of technologies used to develop the products that have been acquired. If products no longer exist, as is the case in many situations, the technologies may have continued to be developed and embedded into new products. Technologies can be tracked using the patent system. In the paper “big tech acquisition and innovation: an empirical assessment” with L. de Barsy, we focus on technologies protected by a patent, and we investigate whether an acquisition by a big tech contributes to their development. For this analysis, we use patent citations as a proxy for the acquirer’s innovation effort. Our main result shows that acquisition increases the innovation effort of the acquirer but only temporarily. After 1.5 years, the number of citations by the acquirer of the patents it has acquired starts to decrease. This suggests that the acquirer further develops technologies, but there is no long-lasting boom in their development. Hence, acquisition does not seem to be a tool to accelerate the development of technologies.

Axel Gautier

| Citation: Axel Gautier, Big Tech Acquisitions And The Ghost Products, Network Law Review, Fall 2024. |

References

- Affeldt, P. and R. Kesler (2021). Competitors’ reactions to big tech acquisitions: Evidence from mobile apps. DIW Discussion Papers 1987.

- Argentesi, E., P. Buccirossi, E. Calvano, T. Duso, A. Marrazzo and S. Nava (2021). Merger policy in digital markets: An ex post assessment. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 17, 95–140.

- Cunningham, C., Ederer, F., and S. Ma (2021). Killer acquisitions. Journal of Political Economy, 129, 649–702.

- de Barsy, L. and A. Gautier (2024) Big Tech Acquisitions and Innovation: An Empirical Assessment; CESifo Working Paper No. 11025 , available at https://www.cesifo.org/en/publications/2024/working-paper/big-tech-acquisitions-and-innovation-empirical-assessment

- Ederer, F. and B. Pellegrino (2023). The great startup sellout and the rise of oligopoly, AEA Papers & Proceedings, 113, 274-78.

- Eisfeld, L. (2023). Entry and acquisitions in software markets. Working paper.

- Gautier, A., & Lamesch, J. (2021). Mergers in the Digital Economy. Information Economics and Policy, 54.

- Gautier, A., & Maitry, R. (2024). Big Tech Acquisitions and Product Discontinuation. Journal of Competition Law and Economics.