The subject of killer acquisitions is capturing the ever-increasing attention of antitrust scholars and agencies. Several reasons explain this trend. One, tech giants are generating gigantic profits that allow them to buy startups without feeling the burn. Two, leaked emails show that big tech CEOs and top executives actively seek to acquire startups early, in order to avoid competing with them. And three, the acquisition of startups often falls below merger control thresholds—as startups may have little to no turnover—which makes the process easy.

But how frequent are killer acquisitions in practice? In Exit Strategy, Mark Lemley and Andrew McCreary highlight that “while 1 in 2 exits was by IPO as recently as the 1990s, only about 1 in 10 is today”. This change gives potential room to more killer acquisitions than before. Lemley and McCreary explain that the change is due to venture funding, as there is a correlation between the number of exits by acquisitions and VC. They note that VCs favor acquisitions to benefit from big tech companies’ network effect. VCs also prefer acquisition over IPOs because acquisitions’ median value is higher. I strongly recommend you read their article or their contribution to the Network Law Review.

What does that tell us about killer acquisitions? My point is that: more acquisitions do not necessarily correlate with more killer acquisitions when there is a strong VCs market.

The term “killer acquisitions” is a misnomer because startups have to agree to be bought. Although they can be under the impression their product won’t be discontinued after the acquisition, the fact remains that they cannot be forced to sell, even by venture capitalists who typically hold minority shareholdings. There are plenty of examples where startup CEOs have refused “impossible-to-refuse” offers, e.g., Mark Zuckerberg famously refused Yahoo’s 1 billion dollar offer. Now, it seems reasonable to think that startup owners are less likely to sell when there are many VCs ready to invest hundreds of millions of dollars and compete on the terms, as opposed to when startups have to make quick profits to survive and/or to rely on just a handful of VCs who can then impose their conditions. In other words, competition between venture capitalists matters. A strong venture capital market reduces the opportunities to killer acquire because it makes VCs compete to offer better conditions instead of imposing their strategy to cash out quickly.

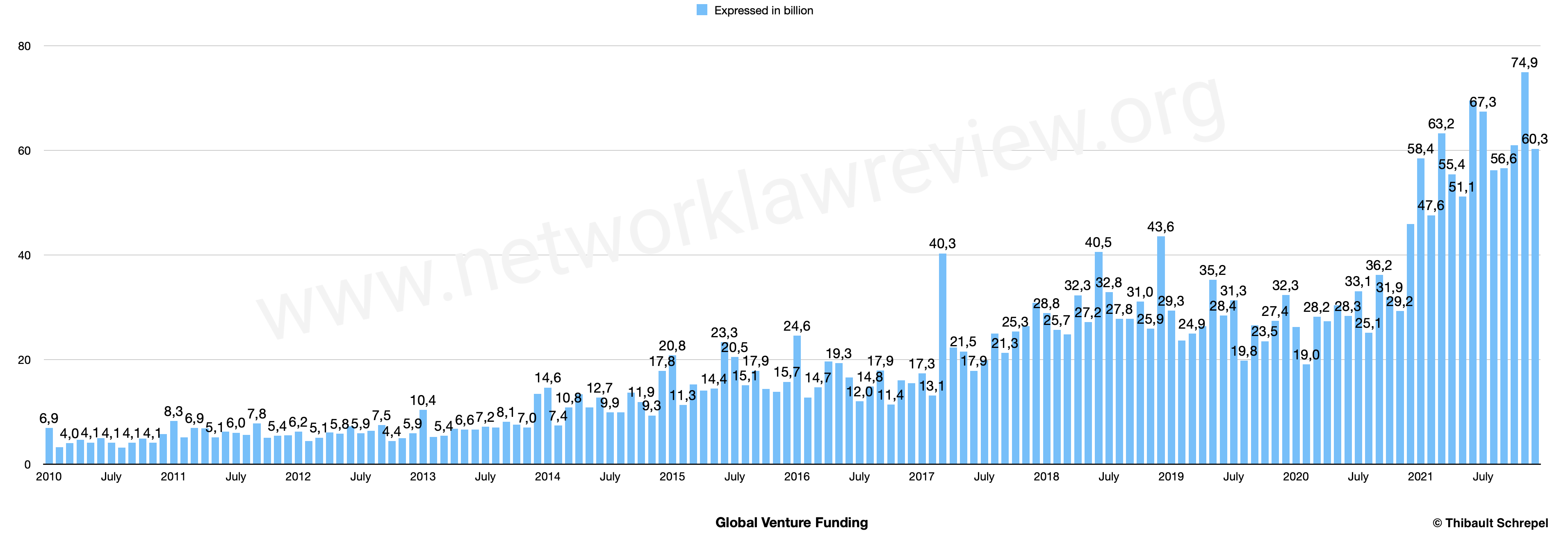

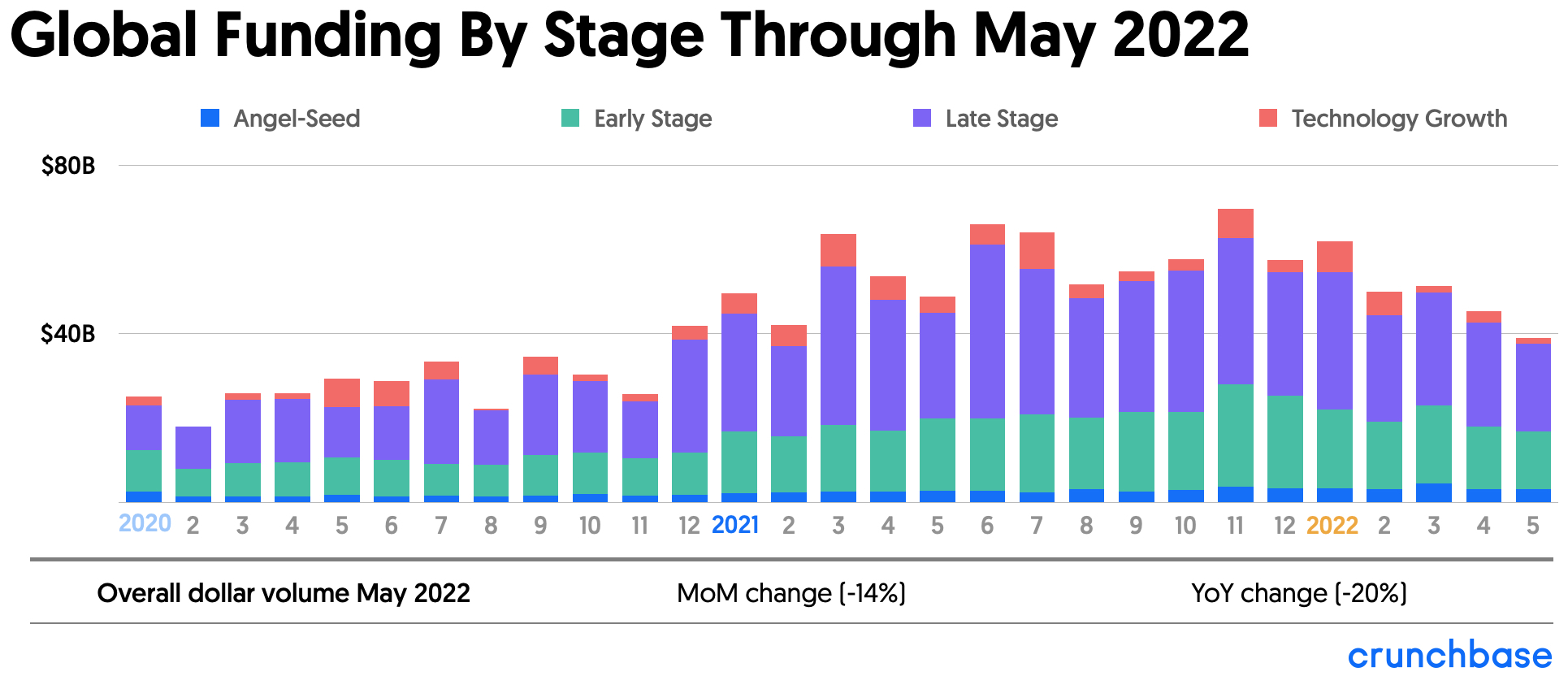

The intuition seems to hold when looking at the numbers. We have never seen so much venture capital investment (i.e., average monthly investments by venture capital firms are 10 times higher in 2021 than in 2011), and we see a correlation between total venture capital investment and late-stage investment. VCs are part of a complex adaptive system: the more VCs, the more startups can bargain, the more VCs (are forced to) invest in long-term strategies; which logically reduce killer acquisitions (made at earlier stages). The fact that we are in the middle of VCs’ golden age suggests that the era of great acquisitions is—at least in part—behind us despite the high percentage that exits by acquisition represents (i.e., around 90%).

Source: Crunchbase. Includes seed, venture, and private equity for venture-backed companies.

Period 2010 – 2021 (to be updated at the end of 2022 when the data becomes available).

© Thibault Schrepel, 2022

Let us consider not one but the example: Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram. The Acquired Podcast lists this acquisition as the best of all time—it generated an absolute dollar return of $152 billion as of March 2020. What was the prime reason Instagram accepted Facebook’s offer? Money. As the Instagram CEO once said, “[w]hen someone comes and offers you a billion dollars for 11 people, what do you say?” But should several VCs offer 1 billion in exchange for a minority shareholding and be willing/forced by competition to keep investing in later stages, it seems reasonable to think Instagram would have turned the offer down. At the very least, some (most?!) companies will.

If that holds true, killer acquisitions may still be possible, but great ones (i.e., acquiring a startup with the potential to completely disrupt the incumbent) may be mostly behind us. Now, to test this intuition, complementary research is needed. I suggest we document whether the exit strategy by acquisition of startups whose VCs have invested hundreds of millions—also in later stages—is as high as the average exit strategy by acquisition. In the meantime, I note that small agencies with scarce resources have asked me what they could do about killer acquisitions while other subjects—for which we have more evidence—are pressing them…

Thibault Schrepel

@ProfSchrepel

I’d like to thank Mark Lemley for his comments on a draft version

| January 2010 | 6,899 |

| February | 3,202 |

| March | 4,008 |

| April | 4,629 |

| May | 4,122 |

| June | 4,980 |

| July | 4,060 |

| August | 3,182 |

| September | 4,075 |

| October | 4,876 |

| November | 4,079 |

| December | 5,713 |

| January 2011 | 8,265 |

| February | 5,097 |

| March | 6,882 |

| April | 6,844 |

| May | 5,138 |

| June | 6,210 |

| July | 6,015 |

| August | 5,545 |

| September | 7,788 |

| October | 5,009 |

| November | 5,433 |

| December | 5,503 |

| January 2012 | 6,181 |

| February | 4,433 |

| March | 5,068 |

| April | 6,042 |

| May | 5,822 |

| June | 7,202 |

| July | 5,869 |

| August | 6,376 |

| September | 7,465 |

| October | 4,383 |

| November | 4,984 |

| December | 5,867 |

| January 2013 | 10,353 |

| February | 5,190 |

| March | 5,440 |

| April | 6,764 |

| May | 6,617 |

| June | 6,615 |

| July | 7,152 |

| August | 6,976 |

| September | 8,113 |

| October | 7,552 |

| November | 6,979 |

| December | 13,392 |

| January 2014 | 14,640 |

| February | 7,404 |

| March | 10,817 |

| April | 13,383 |

| May | 10,857 |

| June | 12,729 |

| July | 9,875 |

| August | 9,917 |

| September | 13,637 |

| October | 11,888 |

| November | 9,300 |

| December | 17,788 |

| January 2015 | 20,789 |

| February | 11,306 |

| March | 15,244 |

| April | 14,061 |

| May | 14,408 |

| June | 23,269 |

| July | 20,453 |

| August | 15,090 |

| September | 17,856 |

| October | 14,382 |

| November | 13,799 |

| December | 15,723 |

| January 2016 | 24,565 |

| February | 12,740 |

| March | 14,668 |

| April | 19,619 |

| May | 19,278 |

| June | 16,585 |

| July | 12,002 |

| August | 14,821 |

| September | 17,870 |

| October | 11,370 |

| November | 16,000 |

| December | 15,465 |

| January 2017 | 17,326 |

| February | 13,116 |

| March | 40,277 |

| April | 22,280 |

| May | 21,528 |

| June | 17,856 |

| July | 19,888 |

| August | 24,930 |

| September | 21,261 |

| October | 25,341 |

| November | 26,362 |

| December | 30,805 |

| January 2018 | 28,848 |

| February | 25,671 |

| March | 24,802 |

| April | 32,281 |

| May | 27,151 |

| June | 40,547 |

| July | 32,841 |

| August | 27,787 |

| September | 27,739 |

| October | 31,040 |

| November | 25,877 |

| December | 43,556 |

| January 2019 | 29,345 |

| February | 23,629 |

| March | 24,946 |

| April | 26,394 |

| May | 35,197 |

| June | 28,374 |

| July | 31,303 |

| August | 19,794 |

| September | 26,560 |

| October | 23,491 |

| November | 27,378 |

| December | 32,297 |

| January 2020 | 26,232 |

| February | 19,041 |

| March | 28,154 |

| April | 27,319 |

| May | 30,361 |

| June | 28,302 |

| July | 33,058 |

| August | 25,114 |

| September | 36,172 |

| October | 31,930 |

| November | 29,230 |

| December | 45,869 |

| January 2021 | 58,432 |

| February | 47,574 |

| March | 63,223 |

| April | 55,402 |

| May | 51,130 |

| June | 69,527 |

| July | 67,342 |

| August | 56,146 |

| September | 56,562 |

| October | 60,945 |

| November | 74,884 |

| December | 60,266 |

***

| Citation: Thibault Schrepel, The Effect of Venture Funding on Killer Acquisitions, Network Law Review, Fall 2022. |