Is the dot really that pathetic?

The Pathetic Dot Theory

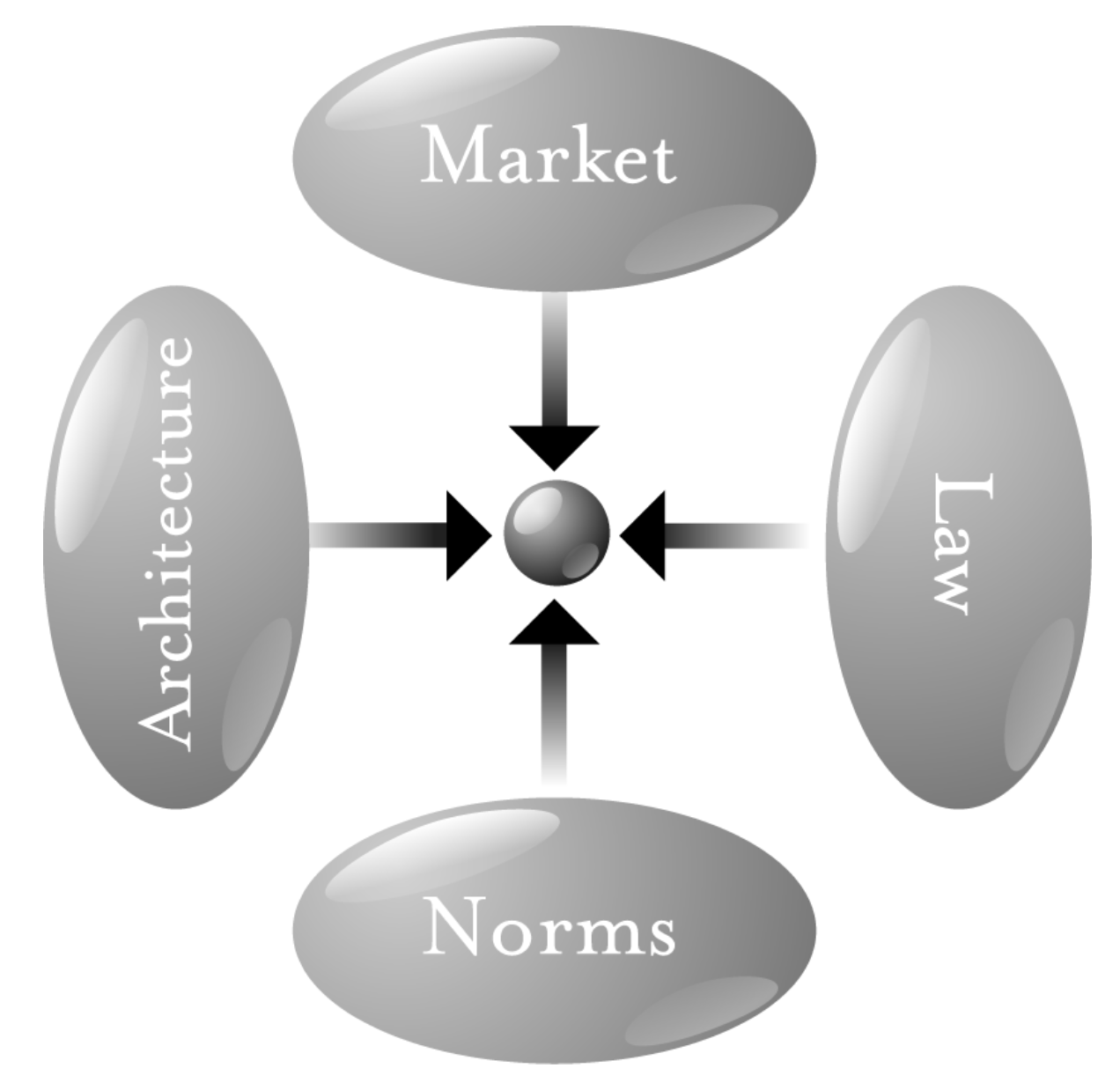

Lawrence Lessig famously introduced the Pathetic Dot Theory in 1999; I quote:

There are many ways to think about “regulation.” I want to think about it from the perspective of someone who is regulated, or, what is different, constrained. That someone regulated is represented by this (pathetic) dot—a creature (you or me) subject to different regulations that might have the effect of constraining (or as we’ll see, enabling) the dot’s behavior. (…) [F]our constraints regulate this pathetic dot—the law, social norms, the market, and architecture—and the “regulation” of this dot is the sum of these four constraints. Changes in any one will affect the regulation of the whole. Some constraints will support others; some may undermine others. (…)

The constraints are distinct, yet they are plainly interdependent. Each can support or oppose the others. Technologies can undermine norms and laws; they can also support them. Some constraints make others possible; others make some impossible. Constraints work together, though they function differently and the effect of each is distinct. (…) We can call each constraint a “regulator,” and we can think of each as a distinct modality of regulation. Each modality has a complex nature, and the interaction among these four is also hard to describe.

Lessig’s theory provides researchers with a framework one can apply to all things digital and non-digital. No wonder it has been quoted and used thousands of times; it’s the kind of theory one can never forget. On a personal level, Code is my favorite law book.

Source: Pathetic Dot Theory (Lessig, Code 2.0, 2006)

The Not-So-Pathetic Dot Theory

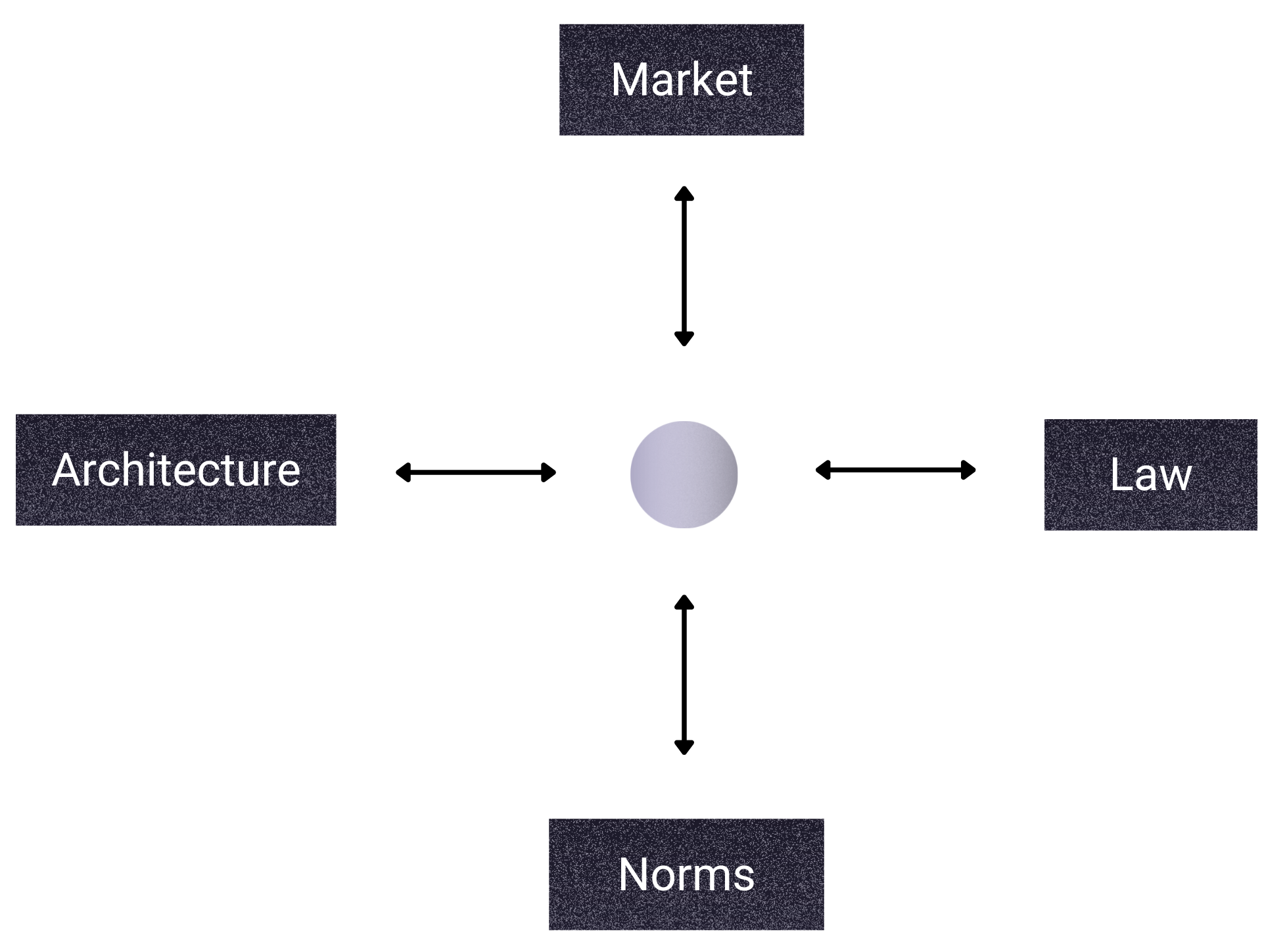

One element The Pathetic Dot Theory is abstracting away is how the dot influences the four constraints. Inspired by complexity theory – the science of how systems react to the context they create — I wish to introduce a slight variation to Lessig’s theory and talk instead of the Not-So-Pathetic Dot Theory.

First, an example. Lessig’s illustrates his theory with the prohibition of smoking. He explains that market (prices), laws (prohibitions), architecture (what’s inside cigarettes), and norms (asking for people’s permission) constrain smokers. My point is this: smokers’ reactions to these constraints influence the constraints. To use the same example, smokers (can) buy cigarettes in a cheaper state, which creates market pressure to keep prices low (market). They (can) lobby regulators to change existing regulations—or influence new ones (laws). Smokers (can) change norms; in fact, it was socially acceptable to have children smoke in ancient culture. And smokers (can) change what’s inside cigarettes by favoring one type of cigarette (type A) over another (type B), thus creating an incentive to offer type A (architecture). The dot is not passive, but a proactive element in the ecosystem. Its proactivity leads to new constraints. The dot then reacts to these new constraints, and so on and so forth. The graph below should be read not as a finite and static game but as an infinite and dynamic game. It represents a complex adaptive system where the dot is not-so-pathetic.

Source: Not-So-Pathetic Dot Theory (Schrepel, 2022)

Applied to the cyberspace, the not-so-pathetic dot theory is also verifiable. Consider blockchain regulation. The dot’s (user) behavior (at the layer 1 or the app layer) influences cryptocurrencies’ prices (market). The dot also reacts to new regulations; some companies famously walked with their feet and went to New Jersey when New York first introduced a Bitcoin license (law). It forced changes in the legislation. We see the same forum shopping on a global scale now, which forces regulators to come up with a new, attractive legal framework as exemplified by the Biden Administration’s executive order (one of its objectives being to “reinforce United States leadership in the global financial system and in technological and economic competitivenes”). The Ethereum dot switched from Proof-of-Work to Proof-of-Stake, thus questioning what is socially acceptable in the ecosystem—is Proof-of-Work still acceptable (norms)? Finally, the dot is reacting to our legal systems by eliminating chock points and single point of failure/control to avoid liability. The dot is forcing policymakers to become more innovative. Again, the dot is not-so-pathetic.

Why Does It Matter?

Andrew Murray (2011) already highlighted that networks of dots force a “dialogue in which the regulatory settlement evolves to reflect changes in society.” In what follows, I wish to look at the (network of) dot(s) from the angle of complexity science.

From the constraints to the dot

One, complexity science offers a target by questioning systems’ robustness. A robust system can soak up random events, which means that despite these events, the nature of the system will stay stable. The more a system is robust, the more its problems are long-lasting. Faced with problematic robust systems—which have gone through turbulent areas without ever changing (e.g., dark web), important changes can and should be made to one (or several) of the constraints. On the contrary, when systems are fragile (e.g., metaverses), it suggests emergent changes in these constraints will address the problem sooner than later.

Two, once you have a legal target (i.e., problematic robust systems), you may question how effective changing the constraints might be. Enters the concept of feedback loop. When feedback loops are positive, a change in the system amplifies and triggers a new state (e.g., childbirth: baby is pushed ➝ increase pressure on the cervix ➝ send a chemical signal ➝ release oxytocin ➝ stimulate contractions ➝ release more oxytocin ➝ baby is born). When they are negative, a change in the system triggers a reaction that ends up returning to the system’s original state (e.g., body temperature: ➝ temperature drops ➝ the body shivers to bring up the temperature ➝ the temperature rise ➝ the body sweat to cool down due to evaporation). Transposed to the legal realm, regulation that triggers positive feedback loops challenges the robustness of a system, but only if these loops are strong enough. Negative feedback loops don’t. Lawyers may want to classify past regulations into these two categories and draw appropriate lessons.

From the dot to the constraints

First, the dot’s influence on the four constraints calls for dynamic thinking: one cannot regulate the dot as if it was pathetic (i.e., unable to react). When the dot adapts to new constraint(s), one should monitor how effective these constraints stay over time. It leads to collecting data (and, before that, to find ways to measure regulatory effectiveness) and to use the data to design real-time, adaptive regulations (i.e., legal dynamism) instead of pursuing the idea of “future-proof” regulation that would be once enacted and always valid. When the dot does not react to changes in (one of) the constraint(s), the situation calls for impacting more constraints, such as designing law and architectural solutions instead of relying on legal solutionism—see “Law + Technology”.

Second, the fact that the dot is not-so-pathetic calls for greater humility in the face of uncertainty. The dot will often adapt in unpredictable ways. We want to ensure we do not deprive the dot (e.g., a technology, a use-case) of what it needs to adapt, survive and flourish against other dots. Dots act as a network in which we see true coopetition. Competition between them must remain fair.

Thibault Schrepel

@ProfSchrepel

| Citation: Thibault Schrepel, The Not-So-Pathetic Dot Theory, Network Law Review, Fall 2022. |